Mental Health and Poverty

An exploration of systemic inequality

I recently created a post on the prevalence of mental illness in the United States.

I started looking more into this topic from a more political perspective. The material conditions by which people are living seem to impact their susceptibility towards mental illness.

In simple terms, socioeconomic factors and mental health are related.

We see this relationship between poverty and mental health is noted by numerous organizations including the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

However, causality for this relationship is often difficult to discern. This relates quite a bit to the limitations of science overall in its ability to be prescriptive.

Nevertheless, the goal of this article is to explore the relationship between mental health and poverty. Not only explore this relationship from a scientific perspective but also from a sociological and political perspective.

Keep in mind a lot of this data and argumentation will apply to Western industrialized countries with an emphasis on the United States.

Poverty is a Normal American Experience

A book I highly recommend others to pick up is Poorly Understood: What America Gets Wrong About Poverty by Mark Robert Rank and colleagues because it truly breaks down our misconceptions about poverty in America.

Americans tend to have this misconception that poverty primarily strikes black and Hispanic folks in crime-ridden urban areas. But the reality is far more shocking.

By looking at the longitudinal data set called the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) we see that the risk of falling below the 20th percentile for income distribution for at least a year for those 25 to 60 is more than 60%.

PSID is one of the most robust longitudinal data sets we have on income and it clearly showcases that the incidence of poverty in America is probably higher than we think.

While a disproportionate number of non-whites are impacted by poverty there is still a high number of whites struck by poverty as well.

In addition, if we look at government assistance recipients a larger percentage of them are white compared to black or Hispanic.

This means that the incidence and prevalence of poverty is a normal experience for millions of Americans not a distinct category for the ‘others’ of society.

Material Conditions Affecting Mental Health

The book Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism by Anne Case and Angus Deaton is extremely telling.

This book is based on a paper on the rise of mortality and morbidity for white middle-aged individuals in America. While I highly encourage you to pick up the book for yourselves, it explores the possible reasons for this rise.

Self-reported declines in health, mental health, and ability to conduct activities of daily living, and increases in chronic pain and inability to work, as well as clinically measured deteriorations in liver function, all point to growing distress in this population.

As previously argued, poverty is a normalized experience in America, and the decline in mental health, especially for certain sections of the population, is leading to the rise in depression, anxiety, suicide, and substance abuse.

On the other hand, employment is negatively associated with mental health decline. Increased income is also associated with improved well-being and mental health.

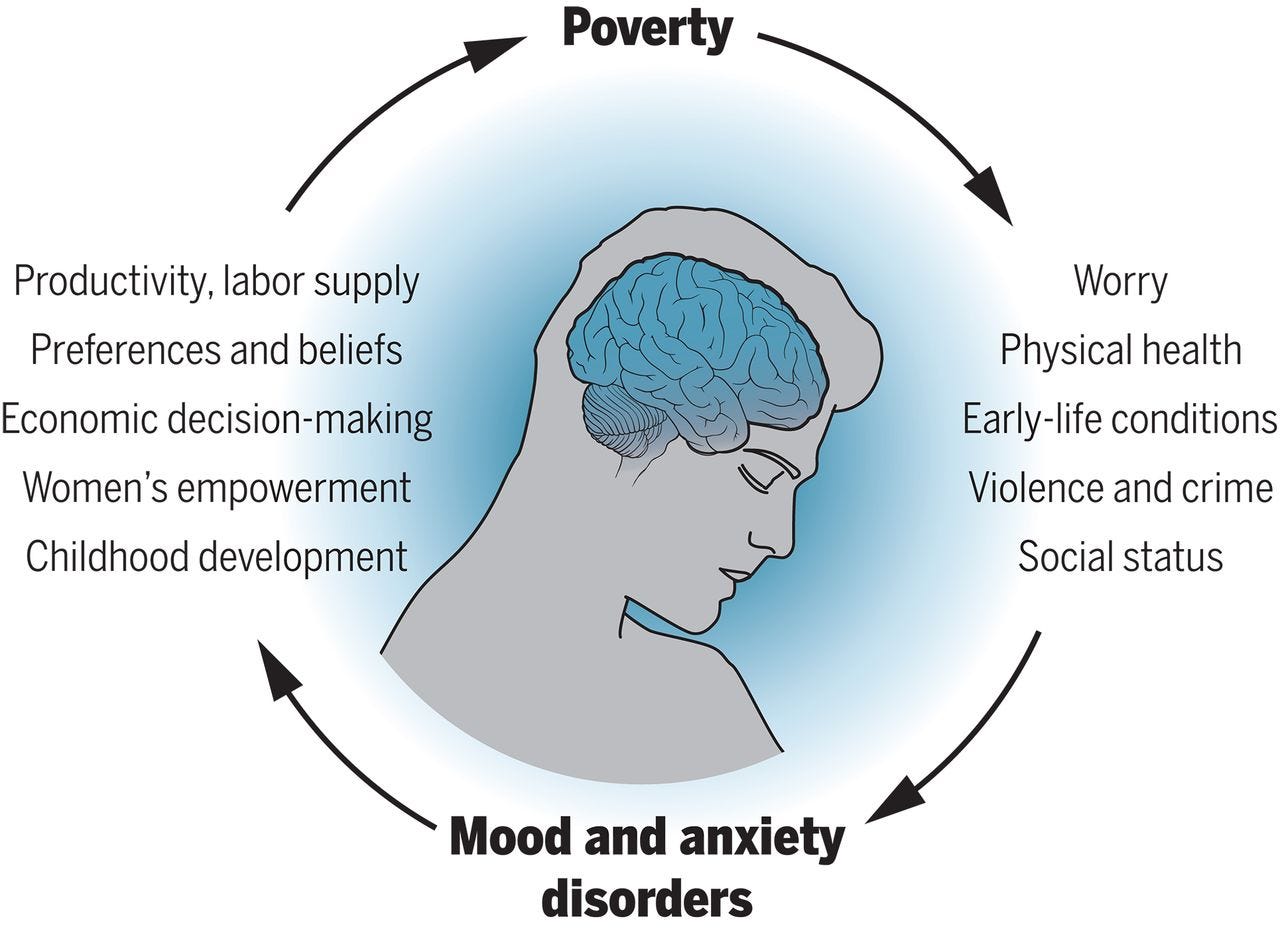

As noted by researchers already, the connection between mental health and poverty is bidirectional. When income decreases measures of mental health worsen, when income increases these measures improve.

What is causing this persistent relationship?

Some researchers have highlighted reciprocal relationships in the causal pathway from poverty to worsening mental health and how worsening mental health can lead to poverty.

According to Ridley and colleagues, there are seven plausible causal pathways connecting mental health to poverty. Keep in mind there is limited evidence for each pathway, I will discuss a few of them below.

Worries and uncertainty- people in poverty often face substantial uncertainty, this can add to life stress making the risk of mental illness more likely.

Environmental factors- individuals affected by poverty are more likely to deal with pollution, extreme temperatures, and sleep deprivation. All of these factors are linked to worsening mental health.

Physical health- having low income often means having limited access to healthcare. Having poor physical health, like chronic disease, is associated with worse mental health.

Early-life conditions- risk from poverty such as malnutrition, stress, and other adverse effects in childhood can lead to a greater risk of mental illness in later adulthood.

Trauma, violence, and crime- people living in poverty are more likely to experience crime and traumatic events. The experience of violence and crime in and outside of the home presents a risk for mental health.

Social status, shame, and isolation- It is plausible that diminished social status resulting from poverty causes or worsens depression and anxiety. Marginalization also increases feelings of loneliness and isolation.

I hope this section highlights the complexities of poverty related to mental health. While pinpointing a causal relationship is difficult, the connection is there.

Mental health and poverty are not merely personal failings, but complex interconnected concepts.

The Lie of Individual Accountability

A person isn’t at fault for being in poverty or being mentally ill.

Unemployment, financial strains, deaths in the family, medical costs, and economic recessions can all lead to unexpected periods of relative poverty.

Factors that are clearly outside of one’s control.

This isn’t said to breed a “victim mentality” but to look at possible solutions for the incidences and prevalences of both mental illness and poverty.

We know that moving those struck by poverty to more affluent neighborhoods leads to improvements in mental health.

Cash transfers reduce incidences of sexual, relational, and physical violence… factors often associated with worsening mental health.

Extreme heat can exacerbate mental illness and overall increased incidences of natural disasters can lead to increases in exposure to trauma.

We could keep going by talking about more environmental and societal exposures related to both poverty and mental health, but the answer is obvious.

We need more solutions aimed at access, care, economic change, and improving the climate for tackling mental health and poverty over a “pull up by your bootstraps” approach.

Final Thoughts

I only scratched the surface by looking at the connection between poverty and mental health.

The connection is clearly there, its direct cause can be debated, but we do have potential solutions for addressing both issues simultaneously.

We need to invest more in mental health resources, as outlined in the previous paper by Ridley and colleagues, mental health treatment in middle to low-income countries helps increase employment and opportunity.

We also need better mental health literacy to help those who need help realize they need help.

In addition to expanding mental health resources and services, we also need to invest in better social safety nets for those in poverty. As poverty is not a moral failing as it is a common circumstance we need systems in place to help individuals in poverty states stay there only temporarily or not at all.

It will take a collective effect to fight off the stave of both poverty and mental illness, but it must be done.